TouchTree

Determining the best touch objects for accessible museum experiences

Overview

Context

Museums typically prohibit visitors from directly touching artifacts or museum objects. Consequently, vision is prioritized as the primary way of engaging with these objects. This creates a boundary for Blind or Low Vision visitors, as well as many visitors who learn and interpret best through tactile interactions. Some museums have begun integrating touch object collections, which allow visitors to interact with select versions of original museum objects.

Challenge

Museums may lack expertise and resources for creating effective, high-fidelity touch objects. Additionally, there aren’t standardized guidelines surrounding best practices for touch object fabrication.

How can we help museums select and produce touch objects for accessible tactile interpretation?

Key Terms

Museum object: refers to tools, clothing, and decorations made by people, which provide essential clues for researchers studying ancient (and contemporary) cultures (National Geographic, “Artifacts”)

Touch object: tactile representations that offer one or multiple interpretations of museum objects (Race et al.)

Decision tree: a flow map that includes questions and yes/no branches, leading the reader to a final outcome

My Role

Interaction designer: I designed and evaluated a prototype of the touch object decision tree.

Collaborators

Timeline

January 2023 - May 2023

Tools

FigJam

WordPress

Results

We used a WordPress website to create a screen reader-friendly interface for users to navigate the touch object decision tree. We also created a visual decision tree to map out all the flows.

The Process

Evaluative Research

Reviewing current literature of tactile graphics decision trees and common types of touch objects at museums.

Ideation Sessions

Designing with museum experts and students producing touch objects.

Usability Study

Evaluating our decision tree with five participants to draw insights and areas to improve.

Evaluative Research

Tactile Graphic Decision Trees

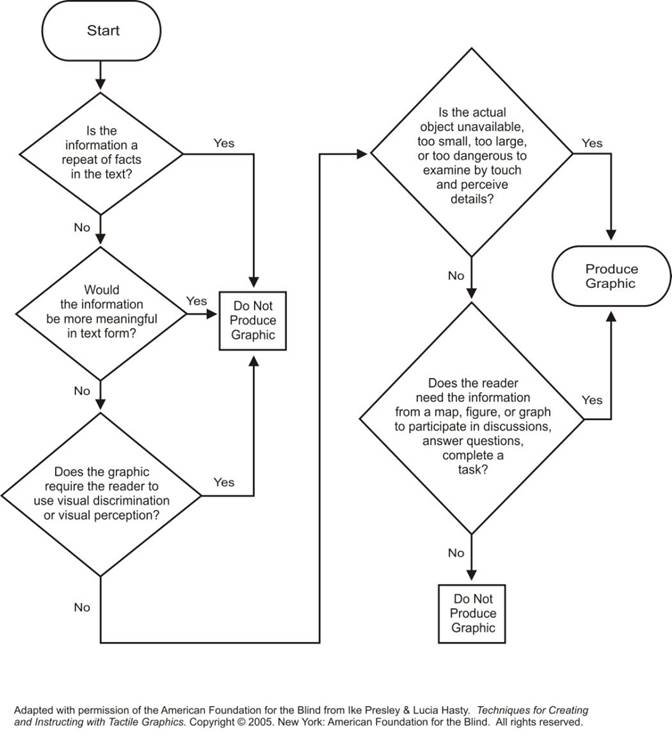

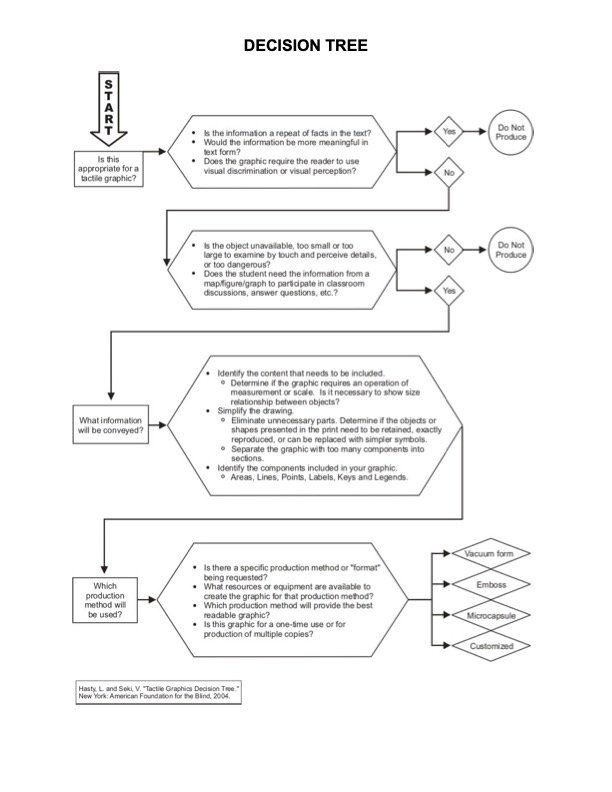

While there are no touch object decision trees in existing literature, there are two popular decision trees for determining when to create tactile graphics and how to product them:

Braille Authority of North America. Nd. Decision Tree. Retrieved May 18, 2023 https://www.brailleauthority.org/tg/web-manual/images/decisiontree.jpg

Lucia Hasty and V. Seki. 2004. Tactile Graphics Decision Tree. New York: American Foundation for the Blind.

Users are encouraged to design tactile graphics for instances when the museum object is:

Unavailable in the museum

Too large or too small to discern effectively via touch

Too dangerous to examine by touch

Conveying information in the form of a map, figure, or graph

Users are encouraged not to design tactile graphics when:

The museum object conveys information that’s a repeat of facts in the description

Information can be more effectively communicated via text

The tactile graphic requires the visitor to use visual discrimination or visual perception

The information derived from the tactile graphic isn’t needed to complete a task

-

Very condensed and easy to scan as a whole quickly

Easy-to-follow arrows

Quickly rules out scenarios in which producing a tactile graphic isn’t appropriate

-

Groups too many questions together - what happens when some questions are “yes” and others are “no”?

Doesn’t distinguish when it’s appropriate to use a particular method of tactile graphic production (vacuum form vs. emboss vs. microcapsule vs. customized)

Variations of Touch Objects

“Understanding Accessible Interpretation through Touch Object Practices in Museums” is a paper written by Lauren Race, Saarah D’Souza, Rosanna Flouty, Tom Igoe, and Amy Hurst, which I reference frequently in my analysis of high-fidelity touch objects. With their research, I’ve essentially worked backwards to group questions that practitioners should ask themselves when determining the best type of touch object to represent their chosen museum object.

-

Benefits: most ideal method; you’re interacting with a piece of history and culture

Limitations: most museum objects are fragile or deteriorate from frequent touch; might still be too small or too large to discern effectively by touch alone

-

Benefits: second most ideal method; can closely match the style and texture of original museum object; good when original museum object is unavailable to touch; can be scaled up or down to discern effectively through touch

Limitations: only suitable for 3D museum objects; might not be possible to acquire a replica: original artist isn’t available or alive, too expensive, culturally inappropriate to replicate with another artisan

-

Benefits: generally for 3D museum objects (e.g. statues, containers); tends to be more affordable than 3D printing; easier to purchase from existing reproduction houses

Limitations: doesn’t convey same sense of texture as original museum object (many models come from the same group of reproduction houses); may be imprecise in comparison to original museum object; may be fragile; may require frequent monitoring of reproduction houses/websites for rare or limited models

-

Benefits: generally for 3D museum objects (e.g. statues, containers); can be scaled up or down to discern effectively through touch; digital files are easily transferable for anyone to print; easily reproducible, can also print individual parts instead of the whole object

Limitations: doesn’t effectively represent flat museum objects; doesn’t convey same sense of texture as original museum object (limited types of plastics used in manufacturing); not always feasible to have access to 3D printers; may be costly

-

Benefits: generally for 2D or flat museum objects (e.g. photos, maps); ideal for representing non-complex content of flat museum object; can be scaled up or down to discern effectively through touch

Limitations: doesn’t effectively represent 3D museum objects; doesn’t convey same sense of texture as original museum object

-

Benefits: accessible; helps contextualize any sensory experience

Limitations: no tactile interaction with museum object; defeats the purpose of visiting a museum

Institutional Structures

A variety of users could use TouchTree. Some levels to consider are:

Curators at small museums, who can make decisions by consulting a close knit team.

Curators at large museums, who may need to engage in cross-departmental communication to answer key questions.

Entry-level positions or museum interns, who need approval from their institution supervisors.

User Journey Map

To contextualize the museum practitioner’s workflow, I created a journey map that captures the lines of communication and research involved to implement a touch object collection.

Ideation Sessions

Assessing Early Drafts

I reviewed an early draft of a touch object decision tree, which was informed by previous research conducted by Lauren Race, as well as existing literature on tactile graphics. I assessed the pros and cons of this draft and posed some questions that should be addressed with future iterations.

-

Good length

Simple language

Specific instructions for dimensions to use for touch object

Avoids repeating questions

-

Ambiguity of touch object solution for museum objects with mixed 3D and flat elements

Overlapping arrows take away from readability

Is it possible for a museum object to be flat and still convey important spatial information?

Are there scenarios where a museum object is both flat and have a complex shape? Or are the contents of a flat object (e.g. photograph) considered complex? Is it ever appropriate to create a 3D touch object in this scenario?

What’s an example of a museum object under the following conditions?

Not commonly found in homes

Needs to convey spatial information

Ideating with Touch Object Designers

I designed a new iteration and informally reviewed it with ModTech, a group of NYU graduate designers working with the Grey Art Gallery at NYU to create variations of touch objects for selected artwork.

Before: tree iteration used for informal evaluation with ModTech, including feedback notes.

After: tree iteration with revisions from ModTech, denoted with stars.

-

“Is the artifact available or safe to touch?” – the term “safe” is unclear or ambiguous.

Asking if the museum object is available/safe to touch BEFORE its dimensionality may be too redundant.

Asking if the museum object is 3D is ambiguous - does the entire object need to be 3D or any part of it?

It would be good to include multisensory solutions if creating a touch object isn’t feasible for the museum.

They don’t anticipate needing to make (2.5D) tactile graphics for entirely 3D museum objects.

-

The first question asks if the museum object is “3D or protruding from a canvas”

Yes means it is 3D, No means it is flat or 2D.

The yes/no branches from the first question should ask if the museum object is available and safe to touch.

To capture the artifact’s key interpretative message, a question was rephrased as “Could the visitor understand the artifact’s core interpretation and context from description alone?”

-

Language needs to be simpler:

Asking if the museum object is “3D or protruding from a canvas”

“Could the visitor understand the artifact’s core interpretations and context from description alone?”

Answering No to this first question means that the object is flat → it isn’t worth touching it directly because the user wouldn’t derive meaning from touch alone. For example, touching a photograph doesn’t directly communicate what the photograph shows.

Exploring Touch Objects

I visited the Intrepid Sea, Air & Space Museum to explore their touch object collection for education tours. I learned a lot about the variation in fidelity between touch objects and how well suited they are to performing different functions, from explaining physical mechanisms to demonstrating the shape and texture of the museum object.

Three touch objects representing a space shuttle: purchased model with moveable flaps (left), Velcro-detachable rocket boosters (middle), fragile model with rocket boosters (right)

Two touch objects representing an aircraft: purchased airplane model (left), handheld fan with soft propellers to represent propelling mechanism (right)

-

I spoke with the Director of Access Initiatives at the Intrepid to identify areas of improvement or clarification for the latest decision tree:

Start with museum object’s dimensionality (2D vs. 3D)

Can the visitor touch the museum object with staff supervision?

“Does the artifact communicate spatial information on a 2D plane?” → unclear; specify that we’re referring to flat canvases

A 3D print isn’t necessarily better than a purchased model, because a detailed model may already be available to purchase or acquire.

3D printed touch objects may be helpful for: whenever effective models are very difficult to come by; constructing unique pieces that require mechanical motion; there is in-house 3D print support (or finances to support 3D printing)

Tactile graphics are more complicated and costly to make than acquiring 3D printed touch objects or models. So, tactile graphics should be reserved for entirely flat artifacts or flat artifacts with some raised or 3D components.

It’d be good to include a separate question for including an additional sensory experience like soundscapes and smell.

-

Having multiple types of touch objects for one museum object can be helpful (e.g. one to describe shape, another to describe mechanical processes).

Lo-fi models are acceptable for explaining the museum object’s mechanical processes (e.g. how it was built, how specific parts function, if it’s safer to touch than the real thing)

If the artifact is safe to touch but too big or too small to effectively discern, handheld-sized models should be made available.

-

Rephrased “spatial information” as “Is it important for the visitor to understand the spatial relationship between elements of the artifact?”

Included a question about the effectiveness of other multisensory solutions.

Included note about supervision for solutions that allow touching the museum object directly.

If the visitor cannot touch a 3D/raised museum object, the tree inquires about commissioning a replica or if the object is commonly found in homes.

Included a question about how well a reproduction of the original museum object can describe relevant mechanical processes (beyond shape, size, texture, etc.)

Included a 3D print solution if existing reproductions nor commissioned replicas are possible.

Revised TouchTree iteration with Director of Access Initiative’s feedback.

Making the Decision Tree Accessible

I sought additional feedback from the Director of McCullouch Historical Hall. One major piece of feedback we received was that the decision tree was difficult to read. The font would print very small in PDF format and it was easy to lose your place in the decision tree. These factors would contribute to information overload.

To improve the readability and accessibility of this visual tree, we decided to restructure the tree onto a screen reader-friendly interface. The visual decision tree would serve as information architecture for the digital interface.

Additional Changes

Simplified the language of all the questions by running them through the Hemingway App.

Modified “2.5D tactile graphic” to just “tactile graphic,” so users aren’t confused by unfamiliar vocabulary.

Changed the question “Does the spatial relationship between elements of the artifact matter?” to “Is it important for the visitor to understand the layout of the artifact?”

Prototype for Evaluation

I locked in the changes for the decision tree and proceeded to translate its logic onto individually linked pages on the WordPress website.

Decision tree information hierarchy used for the usability study.

-

First question should ask about the museum object’s dimensionality to separate two major flows: 3D vs. 2D museum objects

Limit solutions for 2D museum objects to tactile graphics and other multisensory (e.g. auditory) experiences

Follow a hierarchy of touch object solutions for 3D museum objects: artisan-commissioned replica, reproduction or model, 3D print, tactile graphic, other sensory experiences

Always provide a scaled reproduction or model of the original museum object if it’s too large or too small to discern with touch, even if the visitor can directly touch the museum object

-

We borrow the question: Is the object unavailable, too small or too large to examine by touch and perceive details, or too dangerous?

Tactile graphics are an effective solution for flat museum objects and those that need to convey spatial information

-

Tactile graphics aren’t always adaptable for 3D museum objects

Doesn’t offer solutions for touching museum objects directly

-

Question on decision tree

“Yes” links to progress to next branch of decision tree

“No” links to progress to next branch of decision tree

“Go back” links to return to the previous question

A history of each yes/no response from previous questions

-

Solutions page

Dictionary page (the questions have hyperlinked key terms)

Resources page - lists articles and websites that informed this project

Usability Study

Participants

We recruited 5 participants with 5-12 years of professional experience in museum curation and accessibility.

Methods

Task 1 (control): Participants used the TouchTree to determine the best touch object for the Colonoware pot from Cooper River, Charleston County, South Carolina, found at the National Museum of African American History and Culture Collection at the Smithsonian.

Task 2 (experimental): Participants selected a museum object of their choice, from any museum, and used the TouchTree to determine the best touch object for it.

Interview: I conducted a semi-structured interview to learn more about the participants’ overall experience navigating the TouchTree, both the interface and the information architecture.

Topics Addressed

Readability of decision tree questions

Usability of TouchTree website

Effectiveness of dictionary page

Effectiveness and feasibility of proposed outcomes

Reliability of decision tree outcomes

Findings

I used a teleconferencing software to conduct the evaluations virtually. Recordings of the evaluations were saved onto a protected cloud service, which transcribed the audio. I used affinity mapping on FigJam to sort and determine emerging themes. From this, I drew four major key themes.

-

A majority of participants {S1, S4, S5} told us that grouping questions together was confusing to them.

“I think I understand why these are grouped together... but if the answers were different for each question, I’m not sure how I would select that.” -S5

-

All participants expressed that museum practitioners may struggle with deciding which museum objects to use with the decision tree.

“I don’t think there’s anybody who doesn’t want to make things accessible. I think the barriers that get thrown up are: how do we do it? What’s acceptable? How do we pay for it?” -S3

“I think that would help the museum person kind of think and reflect on: what am I trying to reproduce here?” -S1

-

All participants expressed that users aren’t always prepared to answer each question on the decision tree. Curators may need to contact other institutional members for information, such as risk management and collections, depending on the institutional structure of the museum. Budgetary unknowns may require some compromise.

“...If his [original artist’s] son wasn’t able to create that doll, I don’t know that I would be comfortable or that it would be appropriate to ask somebody else in the culture just because different tribes are so distinct and the way people interact [is] so distinct.” -S2

-

A majority of participants {S1, S4, S5} expressed that practitioners may struggle with touch object fabrication without clear guidance.

“What materials do you use for a tactile reproduction? Does it make sense to use raised plastic forming? Does it make sense to use something embroidered?” -S5

“Is it [the touch object] something that’s on a table? Is it something that someone has to bend over for? Is it something you have to reach out on the wall for? How was that experience?” -S1

Key insight: Offering non-tactile solutions, such as visual description and auditory experiences, may discourage practitioners from allowing visitors to touch museum objects directly or building a touch object collection in the first place.

Revised Prototype

Summary of Implementations

Separate all the questions so there’s only one question per page.

Rephrase all questions to be in active voice, not passive voice.

Don’t phrase questions as “is X feasible?” Focus more on the museum object’s attributes.

Before beginning the decision tree, users should review a list of which attributes to prioritize when selecting a museum object to make a touch object for.

Rephrase “No” branches to be “No or Unsure,” so users complete the decision tree. Selecting “Unsure” follows the same path as the “No” branch.

Include specific considerations for each solution offered on the decision tree.

Remove any solutions that are standalone “visual description only” and other multisensory solutions. Only prioritize touch objects. All solutions should still be accompanied with visual description.

Revised Information Architecture

Tree A asks about the museum object’s dimensionality first, then availability.

Tree B asks about the museum object’s availability first, then dimensionality.

I created two versions of the decision tree where the first and second questions were swapped.

Tree A resulted in fewer branches and fewer repeating questions, so we decided to iterate on this version. The fewer the steps, the more likely the user will complete the decision tree.

The dimensionality question, phrased as “3D or raised,” is subjective - what do museum practitioners consider to be raised? For example, some people might interpret painterly texture to be raised, while others wouldn’t. To ensure we catch all use cases of “raised” museum objects:

Simplify the dimensionality question to: “Is the museum object 3D?”

Regardless of its dimensionality, ask if the visitor needs to understand the museum object’s texture. This will prompt catch-all solutions, such as creating a tactile graphic and providing a found material sample.

Final information architecture for touch object decision tree.

Revised Solutions Page

In addition to removing multisensory alternatives, I included specific recommendations and things to keep in mind on each solution’s page. The goal is to provide direct resources for museum practitioners who are planning to take the next steps in implementing a touch object collection for their exhibits.

Reflections

This project helped me grow significantly as a user experience researcher. I practiced research-driven design with every iteration of the decision tree, incorporating feedback from a mix of museum experts and designers who are producing touch objects. In addition, I honed my skills in designing and conducting user evaluations. These experiences have allowed me to parse information, experiences, and data in meaningful ways. I am excited for museum practitioners to work with TouchTree. And I hope that many feel empowered to take the first step in designing accessible museum experiences.

Please feel free to share your feedback or recommendations for TouchTree with the form below!